When I was a child, my parents took me to see the

American Passion Play presented by the Scottish Rite Temple, Bloomington, Illinois (I was surprised to see that it is currently being presented, now in its 85th year). In my childhood eyes, the play’s cast consisted of hundreds of people. The production told the story of the life and death of Christ—from birth to ascension, often quoting famous paintings in their telling of the story.

Drama can entertain. It can teach us lessons. It can make us think. Sarah Ruhl’s play

The Passion Play, currently finishing its run at the Goodman Theatre, is filled with ideas for us to wrap our heads around. I have purposely avoided reading reviews or articles about the play in order to figure out what I think the play is about. To me one of the basic premises of the play is how we fashion and present the Passion of Christ. If the playwright is right, we do it through our visions of ourselves.

This is a play about dreams—what we want, what we fear. Mary (Kelly Brady) in Act I says, “All my life I’ve dreamed of playing the Virgin Mary.” Pilate says in the same act, “I dreamt of fish.” At the end of the play, we are admonished to go home and sleep because only after sleeping fully can we arise with a clear head and see what is reality.

The play is staged on a pine platform stage with large moveable boxes for walls with doors, a window, and a large pine trestle table. Above the walls runs a projection frieze used throughout the play to establish location.

We open to the sounds of the ocean in a fishing village still locked in the medieval view of the world, lying far from the Enlightened World of Elizabeth I. They catch fish here. They gut fish. They even dream of fish. At the end of the act, John the Fisherman who plays Christ strains in silhouette against a red sky pulling in his catch of fish while his dying cousin is carried off by a dream of a school of giant fish.

Our bridge character in Act I is a priest who has come incognito to view one of the last remaining Passion Plays. He becomes the adversary of Elizabeth I.

Throughout the play, a red sky becomes a motif of fear. “I can turn the sky red,” say both the Village Idiot and Pilate) In Act III, Pilate quotes the old adage, “Red sky at night sailor’s delight; red sky at morning sailors take warning.”

In the first act, Christ is portrayed (we are told) by the handsomest and most virginal man of the village (Joaquin Torres). His cousin (Brian Sgambati), limping like a Medieval Richard III or Iago, talks of wanting to kill his cousin—to literally nail him to his cross. “Why does he get to play Christ and I have to play Pilate?” he asks. This conflict becomes one of the motifs of the play--not that of the traditional Christ betrayed by Judas but Christ versus Pilate—Christ whose kingdom is not here on earth versus Pilate whose kingdom is.

Not only are the two men in conflict. The actress playing Mary Magdalene wants to play the Virgin, but the director tells her, “She looks like the Virgin. You look like a whore.” So we find ourselves stuck in roles beyond our own making. But not only are our play parts confusing. Mary Magdalene confesses the desire to kiss another woman—and does. The kissing is used in each act with great power.

The Village Idiot, played with great poignancy by Polly Noonan, wants to be in the Passion, but she is not allowed to until the actress playing the Virgin commits suicide. Then we see her performing the part of Eve—mother of all. The character of the Village Idiot becomes another motif shaped and reshaped in each act. It is she, of course, who sees and knows all and offers us some of the wisdom of the play.

Act I presents the first of the major symbols and motifs of the play: the fish. These larger than human-size fish are carried on like giant floats from a distant Mardi Gras parade. Actors ceremoniously carry the fish in (or are they swimming in?) as if performing in some somber medieval religious rite. The visual effect is stunning.

[A couple of weeks after the production I chanced upon a closeup picture of Peter Brughel’s triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights and from the center panel I was astonished to see the picture at left. At a seminar on the play I was told that this was one of the inspirations for the fish pageantry.]

We should note that the village consists of scores of hidden Catholics, and the symbol of the fish has for centuries been used as the sign of their followers. “Come with me,” says Christ in the Gospel, “and I will make you a fisherman of men.”

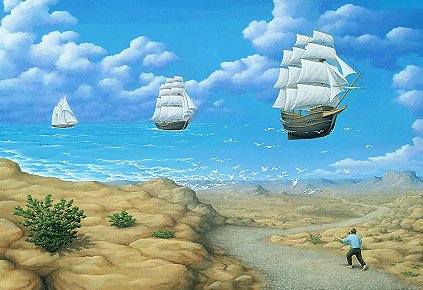

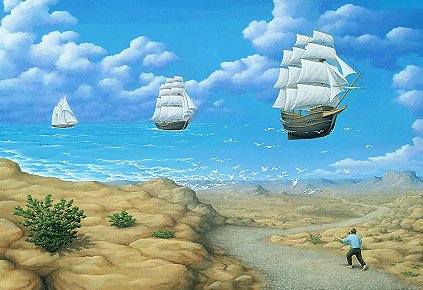

Another motif is a dream of sailing ships from which we desire protection. I assume they were inspired by the Spanish Armada which Elizabeth protected her people from? The march of ships—another ceremony repeated throughout the play--suggests the banners from the medieval ceremonies. It was strongly reminded me of the magic realism of Canadian artist Rob Gonsalves in his painting, “In Search of the Sea.”

The “flying ships” introduces another motif: an obsession with birds and flying. In Act I, the angel of the annunciation is given fantasical wings a la DaVinci and flown against his will up in the air. Are we to see an angel in the first act or perhaps a reluctant holy spirit? In the last act, Christ is flown without wings while op art clouds part to show an op art sun. A man dressed to suggest a bird in the second act can’t fly at all, but merely investigates and leaves—a threatening, vaguely malevolent figure wearing the wings from the first act, but wearing a triangular “bill” which gives the appearance of the gas masks of World War I. In the last act, the daughter who is said to draw pictures of birds, sees her father’s vision of the flying ships.

[When I was a child I went to see Jean Arthur in the Chicago production of Peter Pan. For years I dreamt of flying—my way of escaping my world. But my flying was swimming in the air, like a fish.]

In the production there are three ascensions: the angel of the annunciation in Act I, Christ in Act III and Pilate’s at the end.

Act II finds us in Oberamergau, Germany in the 1930s. The Jews have become the enemy of the “good people.” The Jewish priests are depicted as devils with horned headdresses. Our bridge character becomes a pacifist English spectator who has come to write a book about theatre, with a chapter on the Passion Play. His pacifist views counterbalance the views of Hitler who appears during the rehearsal of the production.

In Oberamergau, the production is only performed by members of families who have traditionally presented the plays. Christ is new—the young man’s father had essayed the role before but is too old now. This young Christ has trouble remember his lines and debates whether he even wishes to play the part.

The young Christ is in love—with the actor performing Pilate who is going into the German army. They have a long kissing scene which is observed by a few officer of the S.S. The officer has a scene where he asks Pilate to feel Mary’s buttocks. He then asks if he is aroused. When Pilate says he is not, he is warned that in Hitler’s army he must function as someone who gets aroused by women.

During the act, the young girl—the act’s village idiot—wants to be part of the production and watches rehearsal. She is told she can’t be part of the play because she is not one of them. When she feeds Christ incorrect lines, she is put in a cage. Later Christ frees her. Shortly after comes a dream sequence where a giant bird—one of the actors in the wings from the previous act and a funnel “beak”—comes and walks around her. He is not a savior, he seems menacingly, even malevolently inquisitive. At the end when the girl is told that she is to be taken away, Christ tells her that she must go, because “your blood is different.” When he attempts to take her away, she struggles and says that she wants to walk on her own. One of the obvious ironies is that it is Christ who gives her up, who betrays—and the other cast members end the act looking accusingly at the audience.

By Act II two questions become prominent:

· What is the role of a leader?

Pilate? Elizabeth? Hitler? Reagan? Christ? In each act, a ruler/leader stops the reality of the play—just as the director does in the inner play—to redirect, to focus to interpose his/her will. We are manipulated—directed if you will—by leaders who stop us from living the lives we want to live. Notice how much each enjoys the “acting” of the part.

Elizabeth in Act I doesn’t want the Passion Play presented because it supports the Catholic view. Hitler decides to allow the work because it disparages the Jews. Reagan welcomes what he sees as wholesome Christian values.

We’ll come back to this idea later.

· What is the role of art in our lives? What is the role of the actor? How does art translate our pain? How does the actor’s obsession with a role change the actor?

The Oberammergau Christ worries because his father’s face glowed and his doesn’t. The director tells him that audiences seeing the play have spent money to attend. They’ll believe his face glows because they’ve paid to believe.

The South Dakota Christ wants to change his acting style to be more real and the new director asks, how will the huge audience then see the emotions without the larger than life gestures? This is, after all, about the production, not about living life.

Research tells us that “Mystery or cycle plays were short dramas based on the Old and New Testaments organized into historical cycles.”

“Unlike morality plays, the cycle plays did not try to influence people to alter their behavior in any way to achieve salvation, but rather they were a celebration of the ‘Good News’ of the salvation preached by the apostles that had been granted through the Passion and Resurrection of Christ.”

The people in each act are presenting the Passion Play. Is this an obvious pun? Is it the Passion of Christ? Or the passion of his people?

In a panel discussion of the play, the actress playing the Village Idiot stated that Act III was the act that on first read through seemed the most complete and ready. It was only as the other two acts became refined that the act became more problematic.

In Act III we are in the 1980s in Spearfish, South Dakota. Pilate, in this case, marries the Virgin Mary and Christ, his brother, betrays him by sleeping with her. There is a sense of a much more episodic storyline since this act covers several years.

For me, the act becomes a descent into the mind of Pilate and we get further and further expressionistically away from reality. Perhaps this is one of the problems that some have with the act. This is not realism and not intended to be. It is perhaps all within the mind and dreams of Pilate.

The act returns to examination of the role of the leader. One of the strongest moments of the play comes when Pilate lies wounded on a battlefield in Viet Nam. Elizabeth I amid all her medieval pageantry enters and says to us:

I cannot fathom why any subject would be willing to die for any leader other than a monarch. What man would die for a leader who was not rushing to the battle-field with him—their blood soaking into the dust together. On the battle-field the monarch and the nation’s blood are one!

In contrast, the Ronald Reagan of Act III describes being a radio sports announcer who had to announce a game he wasn’t even at—he was fed his news through an earpiece. At one climatic point—when the feed is dropped—he makes up what he says. And that’s how he plays at being president. Our modern leaders must learn to act—watch The Queen. Who better to show us that than an actor who became president? Reagan reveals:

I never did serve in the military. But I feel as though I did. I made training films for soldiers, during the war. … Luckily I never sent my men into combat. It is a fearsome thing to do.

Pilate returns home, but as damaged goods, to find his wife and brother and the child he thinks is his but is his brother’s. Has he at this point become our Everyman? [Has he been that all along?] He says at one point, “I don’t want to be in the play anymore.” But in his delusions, he nails his own hand to the cross. So who is this Pilate? Does he represent all of us who think we are good but ultimately wash our hands of Christ’s suffering? Do we all think we want to play Christ until the play gets too close to our own lives?

The theme of infidelity and loss and betrayal runs throughout the act.

But we are also told that we need to hold onto our dreams. We share a need to have someone sleep with us, share our dreams. Pilate’s daughter, who might be Christ’s daughter, ultimately sees the same visions as Pilate—the ships and the fish. She too has listened for the wind. We long for ceremony and religion in our lives, even when we lose touch with God and organized religion.

In the end, the playwright suggests that we should mount the ships of our dreams and fly away holding onto whatever we think is real.

[For the pictures from this production, go to

Photo Flash: 'The Passion Play' at Goodman Theatre.]

Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra was written in 1606. If the boy actor Edmans portraying Cleopatra were dressed as James I's queen, he would have a wheel farthingale, ruff, and stomacher.

Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra was written in 1606. If the boy actor Edmans portraying Cleopatra were dressed as James I's queen, he would have a wheel farthingale, ruff, and stomacher.